Luis Carlos Tovar

Luis Carlos Tovar is a visual artist and educator from Bogotá. He considers art as a vessel for reflection, a catalyst for building resilience, and an agent for inner and outer transformation.

Tovar explores mutable geographies (i.e. displacement), how otherness is created, and the role of memory in the present. He has worked with vulnerable populations in his country and with refugees in Europe. Committed to social justice, he has developed decentralized pedagogical spaces, where participants inhabit their individual and collective journeys. His work integrates different mediums such as photography, painting, mixed media and video installation.

He has exhibited in Buenos Aires, Bogotá, Rome, Paris, Madrid and Pingyao. He recently won the 2017 PhotoEspaña Discovery Prize (Madrid) and and completed a residency at the Musée du quai Branly (2017-18) and at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris (2018-19).

Project

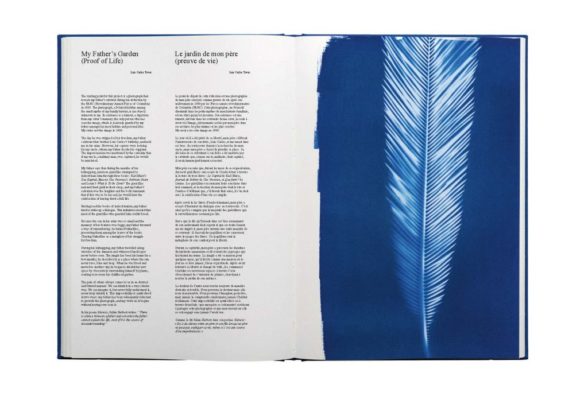

My father's garden (Proof of life)

The starting point for Luis Carlos Tovar’s work is a photograph, but, paradoxically, one that he has never seen. It is the “proof of life” of his father, taken hostage by the FARC in Colombia. Tovar has other traces to fill his father’s silences – the titles of the books he read in the jungle, the turquoise butterflies he kept between the books’ pages, and the Amazon landscapes he tries to recreate in his garden. These enable him to imagine his father’s pain, but never to fully understand it.

“The starting point for this project is a photograph that reveals my father’s survival during his abduction by the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) in 1980. The photograph, a Polaroid hidden among the small myths of my family history, is (an object) unknown to me. Its existence is a rumor, a depiction from my sister’s memory, the only person who has seen the image, which is jealously guarded by my father among his most hidden and personal files.

The day he was stripped of his freedom, my father held me in his arms. He says that during his kidnapping, nineteen guerrillas attempted to indoctrinate him by means of three books: Karl Marx’s Capital, The Bolivian Diary of Ernesto Che Guevaraand Lenin’s What Is To Be Done? My father’s salvation was laughter and the bold statement that, if he were to die, he would do so with the satisfaction of having lived a full life.

A while later, having read the indoctrinating books, my father tried to strike up a dialogue. This initiative revealed that none of the guerrillas guarding him could read.

Because the son in his arms was so small and the memory of his features so blurred, my father invented a way of remembering: he hunted turquoise butterflies (Morpho amathonte), preserving them between the page of the books. Chasing butterflies became a metaphor for his struggle for freedom.

While he was held hostage, my father was taken through stretches of the Amazon and saw landscapes he had never seen before. He contemplated the jungle and when he was finally freed, he began to inhabit places surrounded by plants. Since then, he has been seeking to recreate nature in his new home in the city far from the town of his childhood.

The pain of others is always abstract and indistinct. Our perception of it is extremely elusive. We can imagine it but never fully understand it, never truly inhabit it. This impossibility is symbolized in two ways: my father adamantly refuses to show me the photograph and my work on it begins without ever having seen it.

In The House of the Pain of Others, Julian Herbert writes, “There is silence between a father and son when the father cannot explain his life, although it is the source of misunderstanding.”