Matthias Bruggmann

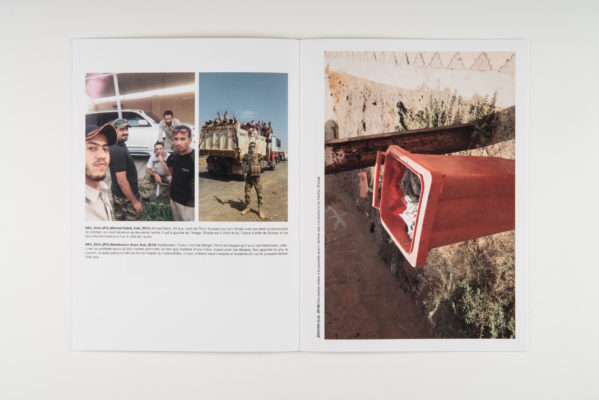

Matthias Bruggmann is a Swiss photographer, born in Aix-en-Provence in 1978. He lives and works on his laptop. He is an alumni of the Vevey School of Photography. His work, which respects the arbitrary norms of photojournalism, tends towards the deconstruction of the norms of representation in the photography of the real, through the representation of complicated situations and places.

He has, amongst others, worked on and in Egypt, Haiti, Iraq, Somalia, Syria and Libya. He was part of the curatorial team for We Are All Photographers Now! for the Musée de l’Elysée, and was one of the cofounders of the contemporary art space Standard/Deluxe in Lausanne.

His work is part of a number of private collections, as well as the public collections of the Frac Midi-Pyrénées and Photo Elysée.

Project

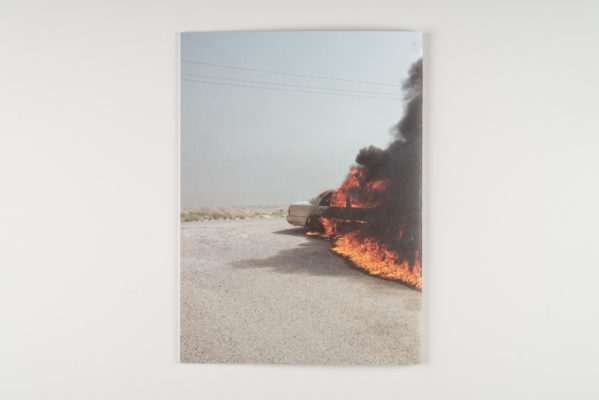

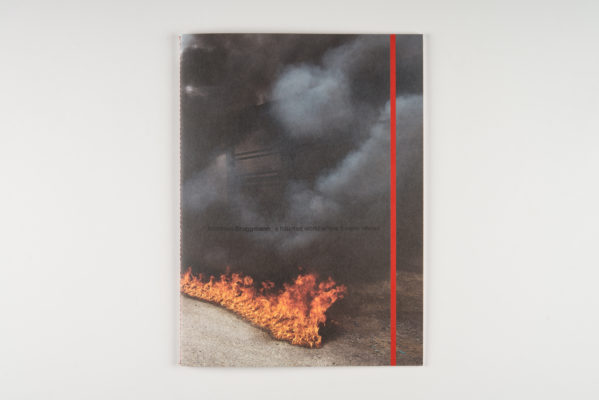

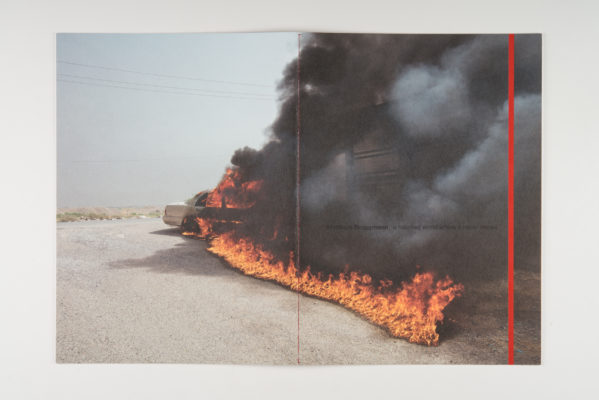

A haunted world that never shows

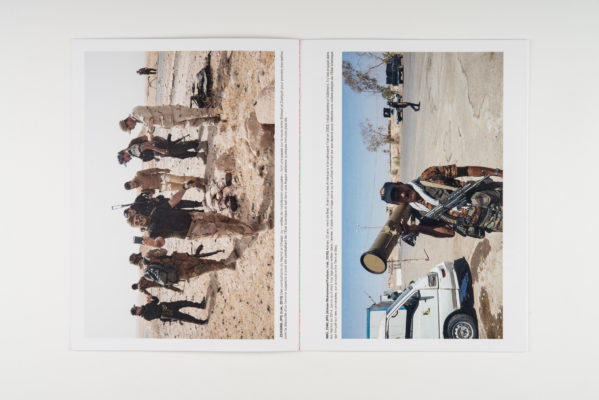

Building on the framework of his prior work on contemporary conflicts, for the Prix Elysée Matthias Bruggmann proposes to continue a long-term photographic project launched in 2012 documenting the conflict in Syria. Respecting the numerous constraints inherent to photojournalism, his work contributes to already produced images with its pointed aim: challenge our own moral assumptions and bring to the surface a greater understanding of the violence that underlies the conflict.

“Formally, my previous work put the viewer in a position where they were asked to decide the nature of the work itself. A scientifically questionable analogy of this mechanism would be the observer effect in quantum physics, where the act of observing changes the nature of what is being observed. My Syrian work builds on this framework.

From a documentation perspective, it is, thus far and to the best of my knowledge, unique as the work, inside Syria, of a single Western photographer, in large part thanks to the assistance and hard work of some of the best independent experts on the conflict. Because of the nature of this conflict, I believe it is necessary to expand the geographical scope of the work.

At its core is an attempt at generating a sense of moral ambiguity. The design of this is to make the viewer uneasy by challenging their own moral assumptions, and thus attempt to bring, to Western viewers, a visceral comprehension of the intangible violence that underlies conflict. One of the means is by perverting the codes normally used in documentary photography to enhance identification with the subject. While perfectly conforming to accepted documentary norms, part of the work aims at eroding the viewer’s implicit faith in my own trustworthiness as a witness, and attempts to force a further reflexion on the nature of what is presented.”