Gregory Halpern

Gregory Halpern holds a BA from Harvard University and an MFA from California College of the Arts. He is a professor of photography at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

He has exhibited internationally and published three books of photographs, including ZZYZX (Mack, 2016), A (J&L Books, 2011) and Harvard Works Because We Do (Quantuck Lane, 2004). He has also published East of the Sun, West of the Moon (Etudes, 2014), a collaboration with Ahndraya Parlato, and he was co-editor, along with Jason Fulford, of The Photographer’s Playbook: Over 250 Assignments and Ideas (Aperture, 2014). In 2016, his book ZZYZX was nominated PhotoBook of the Year at the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, and in 2014, he was the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Project

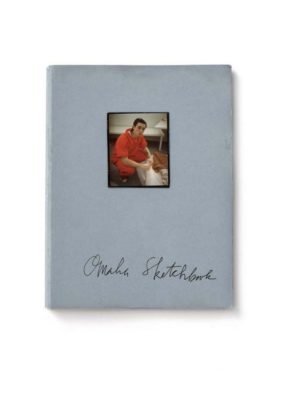

Omaha Sketchbook

Since Donald Trump’s election, Gregory Halpern’s relationship to the hypermasculinity in his country has become increasingly fraught. After an initial album (2009), he is ready to return to Omaha (Nebraska) to photograph the way in which boys are taught to become men. Omaha Sketchbook, a study of place, is also a reflection on power and violence, a meditation on the feeling of inadequacy, the uneasiness and fear experience by someone who was not raised to worship virility.

“As the results of the American presidential election were coming in last November, my wife went into labor with our second daughter. I have always had an uncomfortable relationship with America’s unique brand of hypermasculinity, but since that night, the relationship has become increasingly fraught.

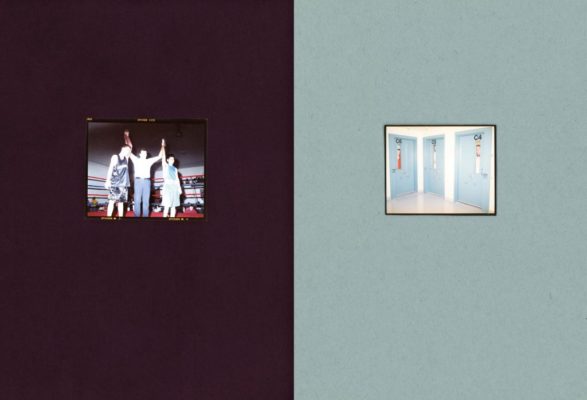

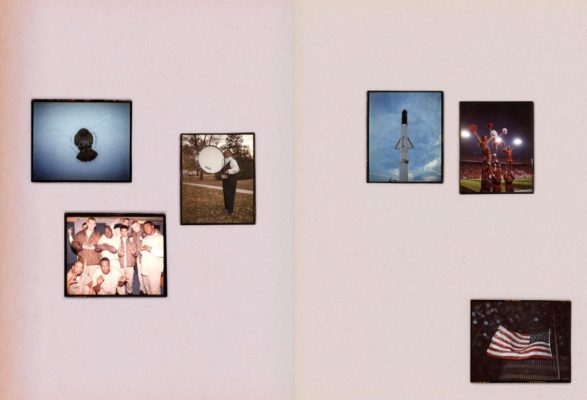

These photographs were taken in Omaha, Nebraska, a city that is home to the biggest American Air Force base. The base’s presence seems to permeate the city, and hunting, football, and the rodeo are popular, as are the Boy Scouts and ROTC (Reserve Officers’ Training Corps).

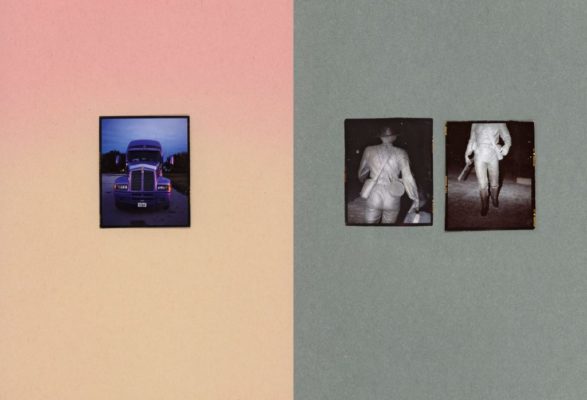

When I am making pictures, I indulge intuitive wanderings and visual attractions. But conscious thought informs the unconscious mind, and while working on Omaha Sketchbook, my vision was increasingly clouded by a growing preoccupation with how the American heartland – in a traditionally masculine, almost Aryan sense of the word – was instructing its boys to become men.

I was the only Jew in my high school and my father modeled a form of gentle, intellectual manhood. Many of my ancestors were killed in concentration camps, and like many Jewish boys with such lineage, I had a complicated, damaged, sense of my masculinity that was plagued by insecurity, identification with the victim, and a sadly inherited sense of trauma. I was jealous of the boys I grew up around, attracted to their seemingly confident and untroubled sense of masculinity. I was also repulsed and frightened by it.

Omaha Sketchbook is a study of place, a meditation on the feeling of inadequacy, and a reflection on American power and violence.”